Thirty years ago, applicants with a history of HIV or a diagnosis of cystic fibrosis (CF) were uninsurable. Today, while many with HIV are offered life insurance, those diagnosed with CF are generally not.

In the past few decades, groundbreaking advances have emerged in early diagnosis, treatment, and management of CF, and those with the condition are now living to age 60 and beyond.1 Why, then, are life insurance companies not yet offering terms to those living with CF?

This article examines the improvement in CF life expectancy and survival, and why insurers might want to consider offering persons with CF limited term life cover.

What is CF?

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder. Two carriers of a faulty cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene have a 25% chance of having a child with the disorder.2 Research indicates that about one in 25 people carry a faulty CFTR gene.3

The CFTR gene produces the CFTR protein, which is responsible for producing sweat, mucus, saliva, tears, and some digestive enzymes. It also regulates the flow of water and chloride between intracellular and extracellular fluid. When the CFTR protein is not produced or produced in insufficient amounts, it results in the buildup of thick sticky mucus, which impairs the function of the sweat glands, lungs, pancreas, and digestive and reproductive systems.1

To date, more than 2,000 mutations have been identified in the CFTR gene, with F508del being the most common. Persons inheriting the same genetic mutation from each parent are said to be homozygous, but someone who inherits two different genetic mutations is said to be heterozygous.4 Some mutations cause more severe forms of the disease than others.

CF is classified into seven different categories based on the patient’s level of functional impairment.

Class I to III: severe phenotype, i.e., little to no CFTR function

Class IV to VII: less severe phenotype, i.e., residual CFTR function 5

Incidence and Prevalence

Approximately 90,000 people worldwide currently live with CF, 30,000 in the U.S. and 50,000 in Europe.1, 6 Its prevalence is 7.97 and 7.37 per 100,000 population in the U.S. and in E.U. countries, respectively. About one in every 2,000 to 3,000 babies is diagnosed with CF, and incidence rates are around 1,000 new cases each year. Incidence varies significantly around the world, most likely due to genetic drift.5, 7, 8

Diagnosis

When CF is suspected in a newborn, a sweat test is carried out between the ages of two days and four weeks to analyze chloride concentration. Sweat chloride testing is now done in conjunction with newborn screening (NBS) tests, which are usually conducted during the first week of life. The test analyzes dried blood spots for immunoreactive trypsinogen, as elevated levels of this digestive enzyme are indicative of CF.7, 9

Sweat chloride concentrations of >60 mmol/L (millimoles per liter) are highly indicative of CF. Those infants with little or no CFTR function generally have very high sweat test results (>90 mmol/L) and are more likely to require pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy.2, 7 If the result ranges from 30 to 59 mmol/L, the sweat test is usually repeated.

Surprisingly, most babies identified with CF are born to parents with no known family history of the disease.

NBS tests can also identify heterozygote carriers of CF or babies with moderately raised sweat chloride levels. Referred to as Cystic Fibrosis Screen Positive, Inconclusive Diagnosis or Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator-Related Metabolic Syndrome (CFSPID/CRMS), individuals with this syndrome are at substantial risk of developing full CF, with studies showing that 10% to 44% of those initially identified as CFSPID/CRMS convert to CF.

Prenatal diagnostic testing can also be conducted, using fetal DNA isolated from chorionic villus sampling or from amniotic fluid cells. Ultrasound screening can also be used at 17 to 22 weeks of gestation to identify instances of fetal echogenic bowel. More recently, a CFTR test has been introduced that uses the cell-free fetal DNA (cffDNA) found in maternal blood to assess fetal CFTR variant status.7

Life Expectancy, Survival, Mortality

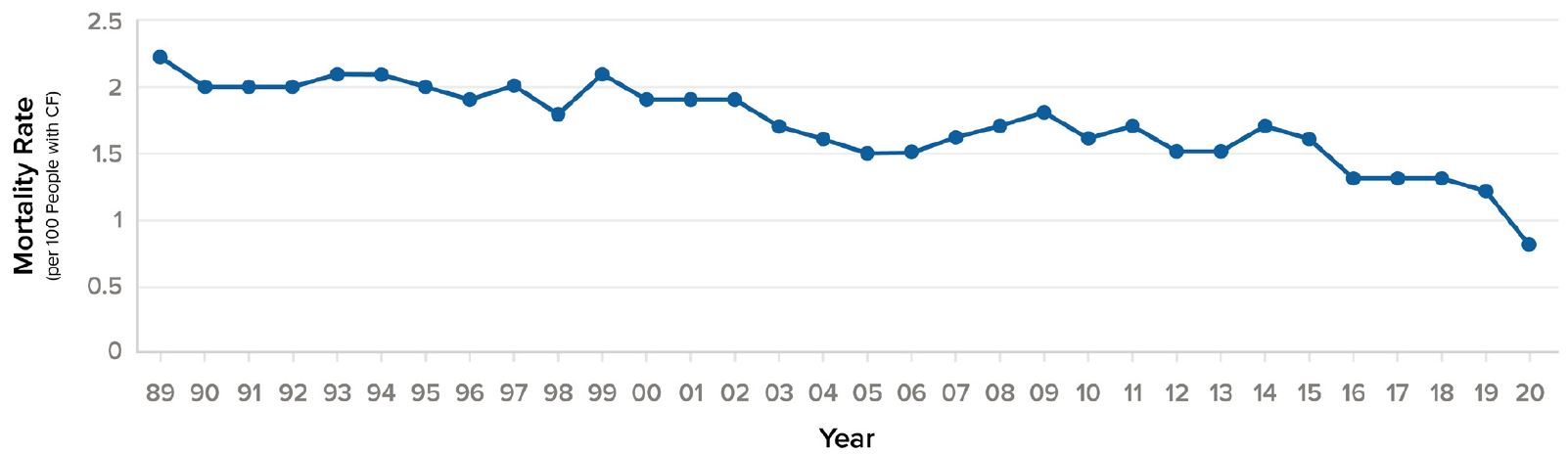

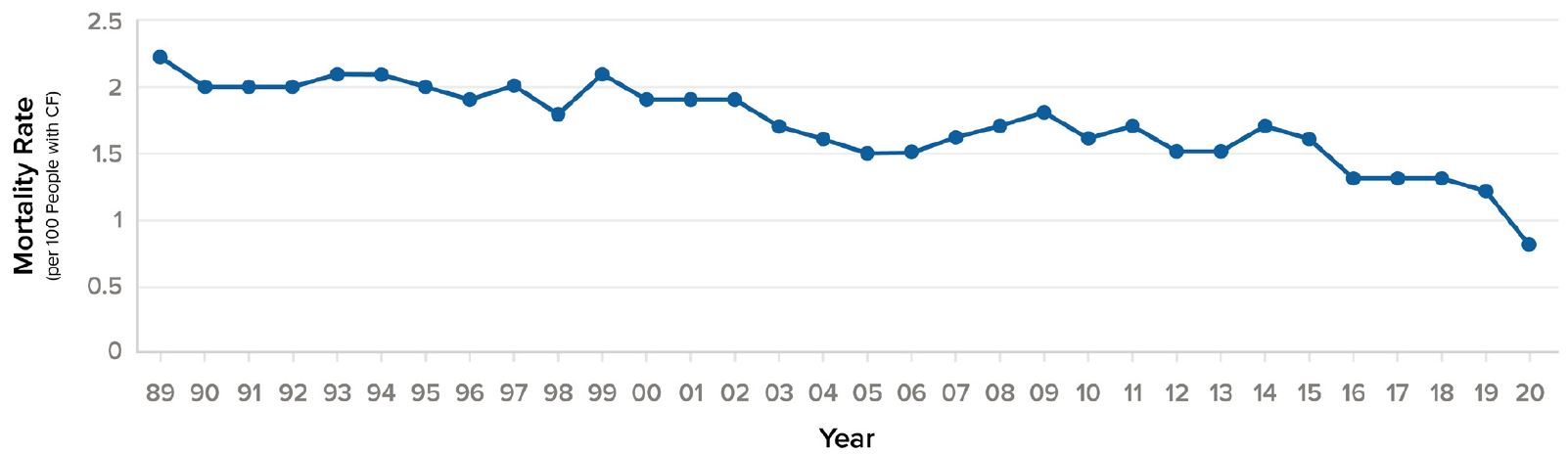

Prior to the 1950s, children with CF rarely lived past age five. By the 1960s, average life expectancy had increased to age 15, and by the 1980s had risen to age 31.10 More than half of the babies born in 2018 and half of people living with CF age 30 and older in 2018 will most likely live into their 50s. This compares with a median predicted survival age of approximately 30 years for those born between 1989 and 1993, a massive leap of 20 years.1, 4 At the same time, annual mortality per 100 persons for CF patients in the U.S. decreased by 50% in just ten years, from 1.6% in 2010 to 0.8% in 2020.

Figure 4:

U.S. annual mortality rate (per 100 people with CF), 1990-20204

Source: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry.

U.K. data shows that for those with CF born today, predicted survival is 50.6 years, and that currently more than 145 people in the U.K. who are living with CF are older than age 60.9 Predicted survival with CF at two, five, and ten years in the U.K. has been calculated at 87.3%, 84.4%, and 80.5%, respectively.6 This compares with a U.K. HIV survival rate in one 30-year national study of 85%, 77%, and 67% at two, five, and 10 years, respectively.11

A 2018 study by Keogh, et al. of 2011-2015 data from the U.K.’s CF registry showed a reduction in mortality rates in the country of about 2% each year, corresponding to a 10-year decrease of 21%. If this decreasing mortality trend continues, children in the U.K. today born with CF should live to age 65 for males and age 56 for females, corresponding to an increase in median survival age of 20 years for males and 15 for females.12