Mental health disorders (MHDs) affect a sizable and growing cohort.4

From 2010 to 2020, their prevalence has risen substantially. For certain MHDs, incidence has doubled in that period: according to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2019,1 about one of every nine individuals worldwide may be affected by an MHD. About 80% of individuals with common MHDs live in low- to middle-income countries,2 with South Asian countries reporting the highest prevalence.2, 3 Many East and Southeast Asian countries have high MHD prevalence as well: In 2017, The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) estimated that in China, MHD prevalence was nearly 10%, or about 124 million.

The economic and social ramifications of high MHD prevalence are significant, with the GBD study estimating its cost at 125 million Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) globally, accounting for around 15% of all Years Lived with Disabilities (YLDs).1 However, in spite of this high and rising prevalence levels, MHDs are far from being addressed optimally, whether by governments, healthcare entities, businesses, or insurers.

To explore appropriate insurance solutions for MHDs, it is important to revisit how MHD symptoms present, to understand today’s clinical journeys for those affected, and the current state of MHD treatment management. With this knowledge, insurers will be better equipped to use existing and emerging medical advances and technologies to strengthen MHD coverage.

MHD Issues

The most current International Classification of Diseases (ICD) manual, ICD-10 (ICD-11 will not be effective until January 1, 2022), and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Medical Disorders, DSM-5, are the two main coding systems used today to indicate symptoms and classify medical diseases and disorders. These broadly utilized systems are based on dynamic observational models and work well with conditions that present with easy-to-recognize physical symptoms, such as pain, discomfort, and/or fever, that make associated conditions relatively easy to diagnose quickly and accurately and then classify.

Diagnoses of many MHDs, however, rely primarily on symptoms observed subjectively by clinicians and on information from patient questionnaires and interviews. MHD presenting symptoms, which can include grief due to loss of a loved one or stress stemming from work or family needs, tend to be more difficult for clinicians to pinpoint as actual symptoms, as they generally lack objective benchmarks such as blood biomarkers or imaging elements. MHD symptom expression can also be more difficult to pinpoint as their expression can depend on gender, culture, economic factors, and geographies.

The comparatively non-specific and frequently non-medical nature of MHD symptoms, and the reality that certain of these symptoms can be present in more than one MHD, can also slow initial diagnosis formulation.5 Final diagnoses are also arrived at more slowly, as MHDs often require longitudinal follow-up for diagnostic confirmation. Determining where an MHD symptom occurs on the continuum from normalcy to pathology is a challenge, as well. As the threshold between the two is not absolute, it may be difficult to assess whether a mental health-related symptom may indicate one or multiple MHDs.

Standard MHD treatment protocols generally include counseling, therapy, and/or community support, but many markets, even some of the more developed ones, may lack sufficient and effective treatment infrastructures. Medications may not exist for many MHDs, or if available, may not be suitable for every patient with the indicated condition. MHD treatment also generally needs to be provided over long time periods (even over a lifetime). Thus, mainstay health and living benefit product designs, with their easy-to-understand coverage triggers such as medication or surgery, capped benefit periods, and reliance on disability outcomes for claims, may need to be adjusted for MHDs.

Additional factors to consider in coverage development are the low awareness of mental health conditions in several countries, along with some cultural barriers to discovery and diagnosis. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) has documented that in the U.S. alone, the average delay between the appearance of a mental health symptom and its treatment is 11 years.6 Cultural barriers and social stigma have also limited targeted long-term studies in some countries, which means predictable and stable statistics for product development in certain markets may be less available.

Challenges and Solutions

The established underwriting categories of diagnostic and medical evidence information, such as presence of symptoms, their severity, and recovery status, can be less effective when screening applicants for MHDs. Yet introducing mental health evaluations into underwriting may not align with consumer demand for simple, fast processes. This may mean that effective underwriting for MHDs could require exploring novel or untapped technologies for risk assessment.

Claims management for MHDs can be challenging as well. As with underwriting, misdiagnoses, evolving diagnoses, and the potential existence of multiple MHDs in a single claimant can lead to complex claims processes that might impact customer experience.

For insurers, the current puzzle is how to develop cost-effective products with sufficient flexibility to cover the range of MHD risks and maintain positive customer experiences. Although past innovations in the MHD space generally did not achieve high adoption rates, consumer expectations have shifted during the past two years, particularly in response to COVID-19.

Innovations in insurtech and healthtech have thus far sparked several changes in the treatment space. Remote healthcare, for example, which emerged as a necessity during the past year, is proving highly effective for both physical and mental health conditions. The scope of care, primarily provided as telehealth, has expanded to include diagnoses, second opinions, therapies, prescription fulfillment, and more. Insurers could address gaps in MHD treatment management by providing coverage for remote treatment in an insured’s home. At the same time, however, insurers need to address new risks such as privacy concerns, and new methods and practices must be developed to optimize alignment of service utilization with therapeutic goals.

Solutions have recently been developed for group MHD cover that offer financial support for online or face-to-face diagnoses or for therapies via cashless reimbursement structures, wellness initiatives, and value-added services. Welcomed by employers, consumers, and other stakeholders, these advances may carve new paths for technology-driven, customer-centric MHD solutions for individuals.

Wellness services by themselves are also emerging as an area of innovative and collaborative insurance offerings for mental health needs, primarily via mobile apps or interactive activities such as online coaching, webinars, coping tools, and community support. The scope of these services, indicated in Table 1 (below), encompasses strategies around mindfulness in order to manage symptoms such as: depression, anxiety, stress, difficulty with sleep, and chronic pain; recovery from drug and alcohol abuse; coping with post-traumatic stress disorder; and more.

Table 1:

Apps and Activities Available for MHD Management and Support

Self-management | User can self-enter and track symptoms and ways to manage health, such as medication reminders |

Improving thinking skills | Help with cognitive remediation |

Skill training | Help users learn new coping strategies and skills |

Illness management, supported care | Users connect with peers and care providers in real time |

Passive symptom tracking | Smartphone sensors enabled to track patient behavior patterns |

Data collection | Enables passive tracking of large cohorts by researchers |

Research via smartphone | Using smartphones to enroll and track study participants and recommend treatments |

Source: National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH)14

Gaining a better understanding of MHDs may also lead to more effective insurance coverage. One possible product development path may be to look at addressing specific subsets of MHDs. One such subset has been developed by The Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP),7 a World Health Organization (WHO) program that focuses on the need for resources to address the burden of mental, neurological, and substance abuse problems. The subset, which includes depression, bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, dementia, intellectual disabilities, and developmental disorders such as autism, are deemed priority mental and neurological disorders. If extensive long-term research is undertaken for these priority conditions, results could strengthen product development.

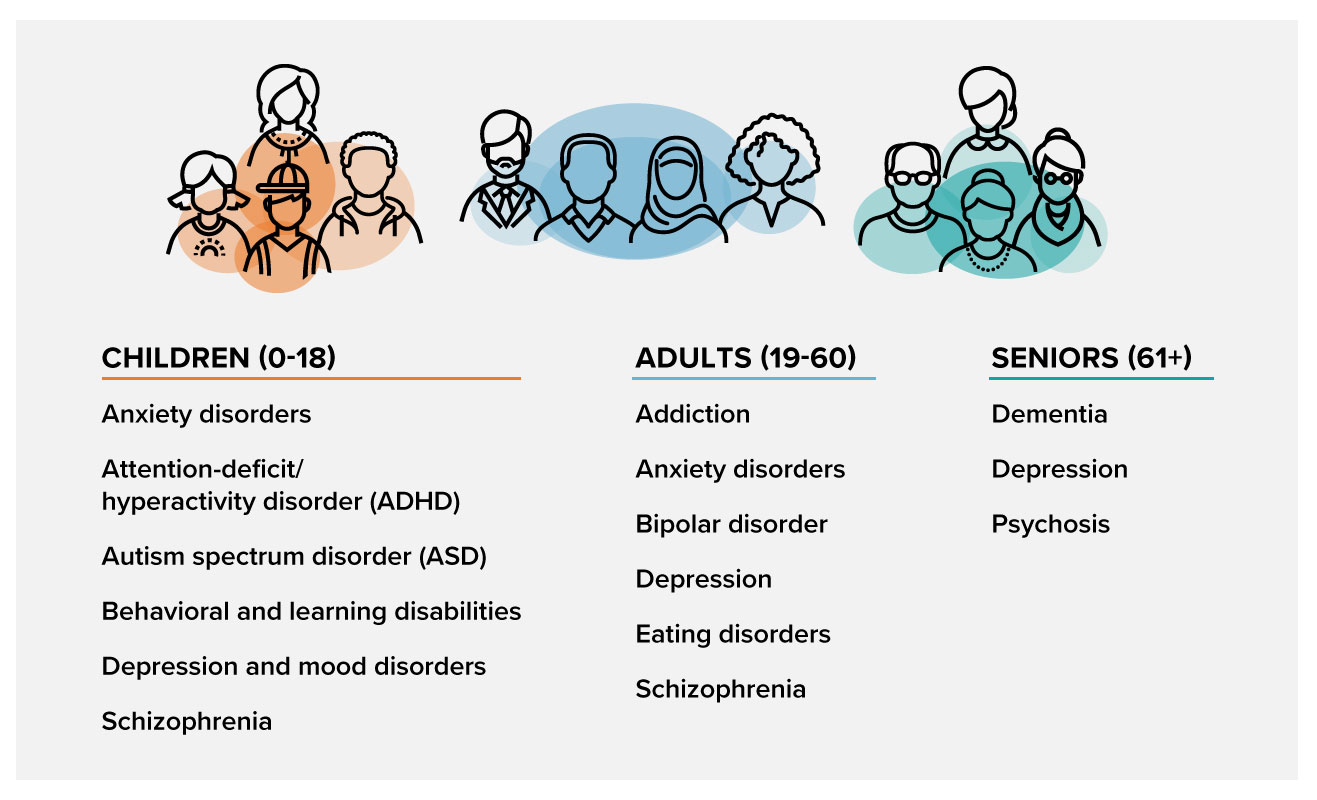

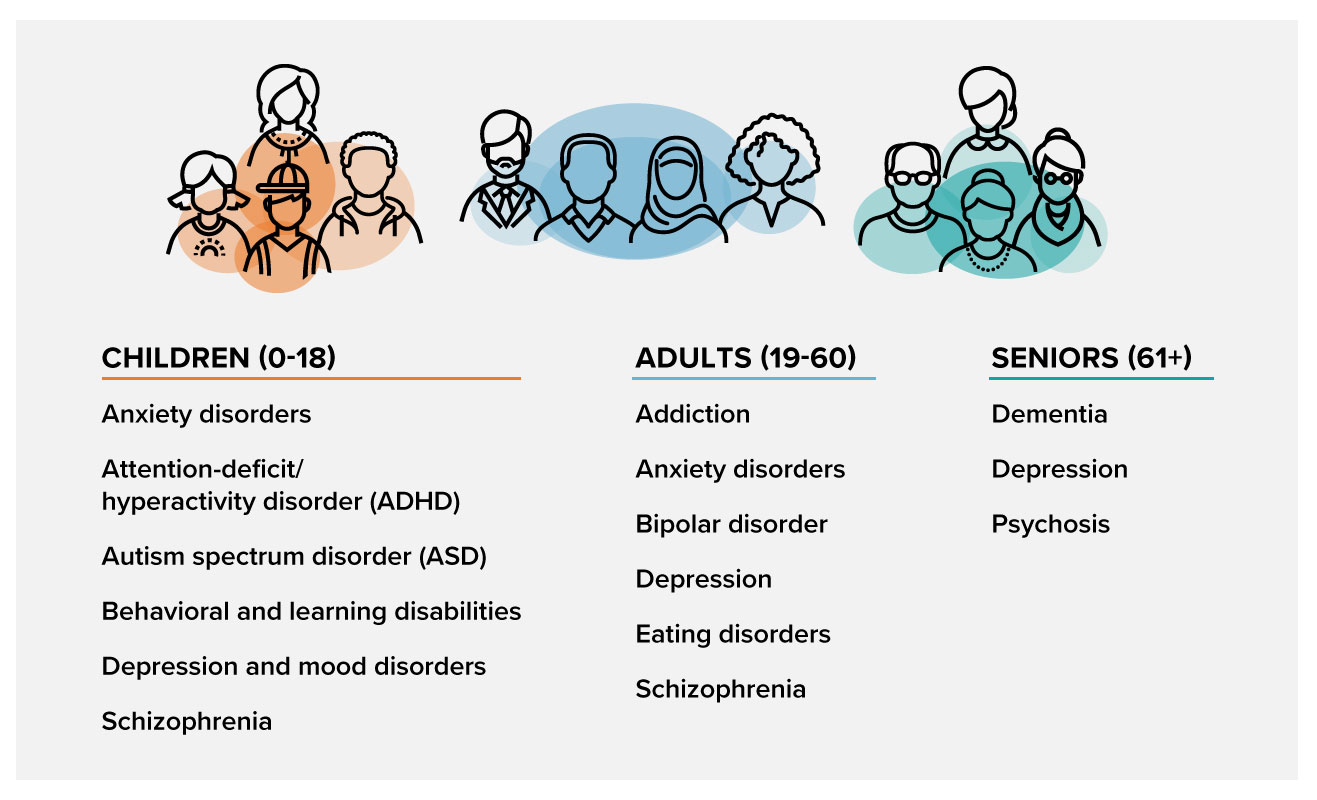

Another possible path for insurers might be to look at conditions with high prevalence in specific age groups and use them as a basis for crafting solutions. Table 2 (below) lists many different mental health disorders by prevalence in their age cohorts.

Table 2:

Common MHDs by Age Cohort

Focusing on treatment cover is yet another strategy. MHD patients require substantial support for their treatment journeys, from early detection to long-term therapies. Today’s broad public health policies emphasize early intervention strategies for MHDs to avoid the more severe stages, but intervention also needs to take place in ways and environments that are physically and psychologically safe for patients, especially in countries or communities where social stigma around MHDs is an issue. Support, too, must be available for monitoring, prevention of recurrences, and coping with suicidal tendencies, to keep MHD patients financially and socially engaged throughout their treatment. Benefit solutions that align with MHD treatment journeys will tend to be more beneficial and successful.

Looking Ahead

With the changes in treatment provision due to COVID-19, now might be a good time to align MHD cover with the natural courses of these conditions in ways that can improve effective management of treatment and costs. Products can be structured to address the challenges of identifying and diagnosing MHD symptoms and facilitate coverage of appropriate long-term treatment modalities. Meaningful, high-value solutions could incorporate appropriate longer duration payments for ongoing treatment and support and include, along with need-appropriate lump-sum benefits, value-added services such as wellness solutions.

As insurers analyze how they can provide healthcare products with benefits and multiple touch points that can enhance customer well-being over a policy term, facilitating good MHD cover can provide opportunities to develop such a framework. However, doing so means assessing MHD risk appropriately and then evaluating products and their benefits for suitability. This analysis may span underwriting, onboarding, and claims processes, and involve ensuring these processes conform with applicable anti-discrimination laws for better outcomes. Insurers could also consider structures such as embedding benefits into products rather than offering them as standalone and/or voluntary cover; broad-spectrum cover for more minor events; and benefits that would enable a product to handle longer-duration needs instead of mandating substantial up-front payments.

To simplify underwriting and claims customer experiences, new technology interfaces can also be explored and integrated into products. Development and use of dynamic onboarding platforms and implementation of more agile procedures can strengthen product-appropriate underwriting and claims processes as well. For example, tele-assessment of cognitive impairments is already being used in some markets. Could insurers incorporate technologies that could screen applicants for MHDs or for the possibility of their presence in a quick, cost-effective, and efficient manner? If so, the same tools could also be deployed for risk assessment and wellness interventions. Similarly, insurers might incorporate cover for tele-consultations and second opinions for claims to strengthen claims processes.

Medical advances in the field of MHDs are also promising for the future of MHD cover. The National Institute of Mental Health's Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) Initiative,8, 9 for one, is collecting and integrating data on genetics, biochemistry, brain circuitry, and neuroimaging, as well as on behavior and advances in modalities such as psychogenetics10 and psychoradiology,11, 12, 13 to develop a framework for improving the understanding of MHDs. Such research may increase the understanding and relevance of neurobiologics in MHDs, which could alter the clinical diagnostic approach and spawn novel therapeutic interventions that might positively influence how insurers approach MHDs.

All in all, insurance solutions for MHD needs appear to be evolving in the right direction. Insurers might also benefit from further examining their potential role in strengthening cover by supporting new and workable treatment solutions while remaining cognizant of existing and emerging challenges and risks. Companies will need to develop, test, and then identify the designs and benefits that will have the most potential of resonating with distribution forces and consumers alike.

RGA is well-positioned to help you navigate the complex, dynamic, and evolving MHD landscape. Our experts can partner with you to develop MHD solutions and to support vigilant monitoring of new medical, epidemiological, and behavioral developments for continuous assessment of risk and product relevance. For more information, please contact Dipali Jawalkar and Minnie Yu.

|